Blackface and a History of Amnesia

By Ayanna Thompson

When my son, Dash, was in the third grade from 2011 to 2012, he attended a private school that prided itself on its academic rigor. In fact, each eight-year-old student was required to do a year-long research project on an influential person in history.

As the culmination of their research, the kids had to make a poster that highlighted their person’s life and accomplishments, and then dress up as their person and answer questions as if they were the famous person during the poster presentation. It was a lot of work, and the presentations were impressive. That year there were astronauts and entertainers, politicians and athletes, humanitarians and playwrights.

And there were also several little white children in full-on blackface makeup—they were “Martin Luther King Jr.,” “Serena Williams,” and “Arthur Ashe.” As I walked around the room, looking at the posters and interacting with the famous, historical people, I was stunned when I saw the first blacked-up child.

“I recognized that the principal’s ignorance [about blackface] was symptomatic of the American amnesia with regard to racism and racial violence.”

Attempting to keep my face neutral, I asked questions about “Martin Luther King Jr.’s” life and praised the student for her hard work. It was clear that she had immense respect and reverence for Dr. King—he was her hero. She beamed through her blacked-up face, proud to be him. I stared on in an attempt not to register my horror and dismay.

After taking this in, I immediately went to find the school’s principal to ask what was happening. Was makeup allowed? Encouraged? Did the teachers facilitate this? Were the parents involved? What conversations had they had about cross-racial impersonation, even if this all occurred under the auspices of hero worship?

The principal seemed not to understand what I was saying—that the children’s performances were veering dangerously close to blackface. He seemed confused and indicated that he thought I was making a tempest in a teapot. I could see in his eyes that he was reading me as an irrationally angry black woman, and then he asked, “What is blackface minstrelsy anyway?”

I was gobsmacked by the question. In fact, I was quickly becoming the angry black woman he thought I was, wondering why I should have to explain American history to an American educator at a tony private school. Why didn’t he know this already? Why was it my job to teach him our shared history? Why did I have to pay this black tax on top of the tuition I was already paying?

I was enraged by his ignorance because it made starkly visible the inequality of our experiences. I had to know this history because it affects me and my children in the twenty-first century; he did not because of his white privilege, which was expressed through an implicit notion that this history did not, does not, and will not impact him or the white charges in his private school.

“The book is a defiant and material act of remembering our collective American history.”

When my anger was less blinding and began to subside (I was a rationally angry black woman, after all!), I recognized that the principal’s ignorance was symptomatic of the American amnesia with regard to racism and racial violence. The history is difficult, and the solutions are neither readily apparent nor easily achievable; so forgetting, while not necessarily natural, is widespread, pervasive and common. And forgetting blackface minstrelsy—a performance tradition from the early nineteenth century—is easy to accomplish because it happened back then (i.e., it’s over and has no resonance in today’s world).

The principal’s reaction, while unfair, was actually normal. But I am not content with this normal state of being. I need to be able to make it as impossible for him to forget as it is for me—it is both of our history after all. I need to be able to combat the extensive drift toward amnesia. I wrote my book Blackface as an attempt. The book is a defiant and material act of remembering our collective American history.

One last note: Not one of the children of color in my son’s class applied racial prosthetics to look white. Why not? Were they less committed to the fidelity of their representations? Did they know something the white children did not? Or, did the white children know something the black and brown children did not? These questions haunt my book and fueled my writing of it.

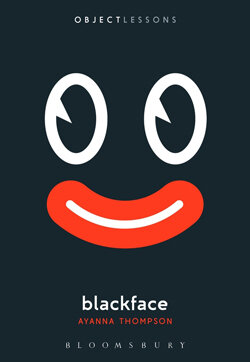

This essay is an adapted excerpt from Blackface, part of the Object Lessons books series published by Bloomsbury.

Read our "Story Behind the Story" with Thompson to learn more about how and why she wrote the book.

Ayanna Thompson is a Regents Professor of English at Arizona State University, and the Director of the Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies. She is the author of the just-published book Blackface.